There’s a new Final Rule on permitting reform for major transmission lines. From the NY Times..

Administration officials are increasingly worried that their plans to fight climate change could falter unless the nation can quickly add vast amounts of grid capacity to handle more wind and solar power and to better tolerate extreme weather. The pace of construction for high-voltage power lines has sharply slowed since 2013, and building new lines can take a decade or more because of permitting delays and local opposition.

The Energy Department is trying to use the limited tools at its disposal to pour roughly $20 billion into grid upgrades and to streamline approvals for new lines. But experts say a rapid, large-scale grid expansion may ultimately depend on Congress.

****************

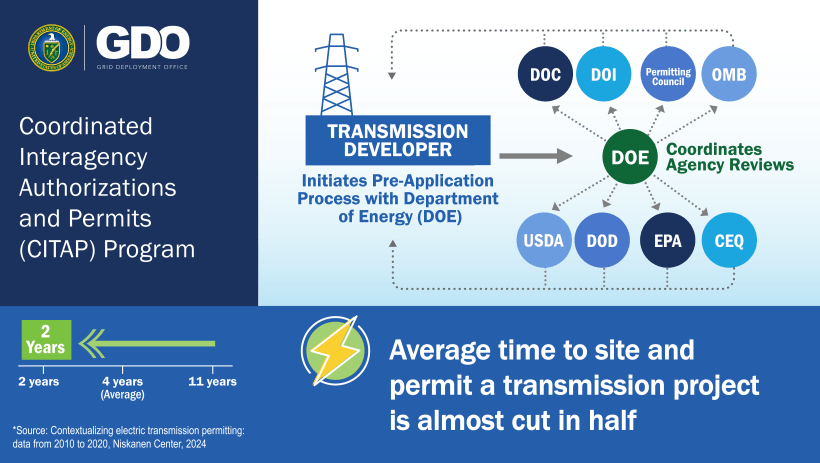

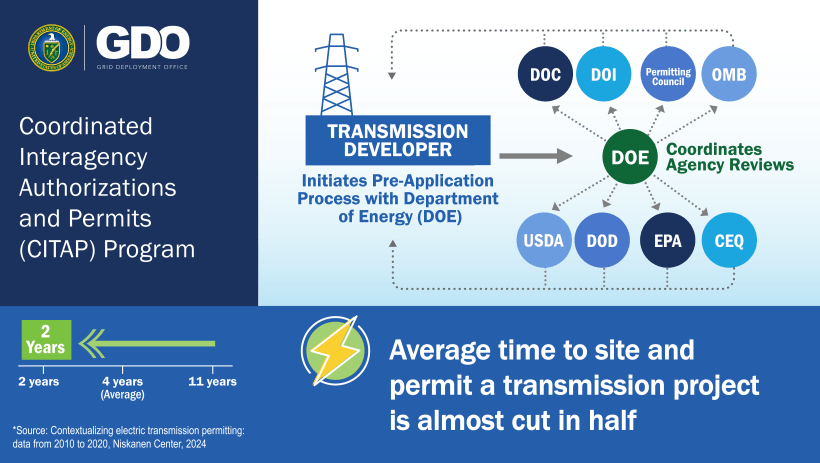

Under the rule announced on Thursday, the Energy Department would take over as the lead agency in charge of federal environmental reviews for certain interstate power lines and would aim to issue necessary permits within two years. Currently, the federal approval process can take four years or more and often involves multiple agencies each conducting their own separate reviews.

“We need to build new transmission projects more quickly, as everybody knows,” Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm said. The new reforms are “a huge improvement from the status quo, where developers routinely have to navigate several independent permitting processes throughout the federal government.”

The permitting changes would only affect lines that require federal review, like those that cross federally owned land. Such projects made up 26 percent of all transmission line miles added between 2010 and 2020. To qualify, developers would need to create a plan to engage with the public much earlier in the process.

*************

This seems like the old “if we only engaged people sooner, they would like this project” thinking.

Here’s the requirement.

DOE requires transmission developers to develop a comprehensive public participation plan before they apply for federal authorizations and permits. This is a new and novel approach to transmission infrastructure development and will ensure that communities and key stakeholders are identified and accounted for at the onset of the permitting process.

Back to the NYT story:

Experts said the change could be significant for power lines in the West, where the federal government owns nearly half the land and permitting can be arduous. It took developers 17 years to win approval for one major line, known as SunZia, that was designed to connect an enormous wind farm in New Mexico to homes and businesses in Arizona and California.

And yet, it is in litigation still as we shall see below. And not mentioned.

“Federal permitting isn’t the only thing holding back transmission, but if they can cut times down by even a year, and if we have fewer projects that take a decade or more, that’s a big win,” said Megan Gibson, the chief counsel at the Niskanen Center, a research organization that recently conducted two studies on federal transmission permitting.

The rule would not affect state environmental reviews, which can sometimes be an even bigger hurdle to transmission developers who are facing complaints and lawsuits over spoiled views and damage to ecosystems.

Nor litigation of course, which can also be a hurdle. But speeding up the progress toward litigation should help.. unless, of course, people speed up the analysis and litigants can find more questions to exploit. I think this is the argument folks have used about NEPA for projects they consider to be less desirable. I think we know this terrain. It all depends on the presence of Groups With Resources Likely to Litigate.

Congress has also given federal regulators the authority to override objections from states for certain power lines deemed to be in the national interest, a potentially contentious move. The Biden administration has yet to wield this power, though it is working to identify potential sites that could qualify.

“We’ve been trying to maximize every nook and cranny of what we can do right now,” said Maria Robinson, head of the Energy Department’s Grid Deployment Office.

Still, experts say, there is only so much the administration can do to expand the grid without help from Congress. To date, lawmakers have struggled to agree on ways to reform the system.

In the House and Senate, Democrats have proposed various bills that would mandate greater grid connectivity between regions or place more permitting authority in the hands of federal regulators. But some utilities and Republicans have criticized those proposals as taking control away from states.

Elsewhere, energy companies have asked Congress to enact permitting reforms that would set stricter time limits on challenges and lawsuits from opponents of new projects. But environmentalists are wary that those changes could also benefit fossil fuel projects such as pipelines.

At a recent conference in New York, David Crane, the under secretary for infrastructure at the Energy Department, said that if he could “wave a magic wand” he would ask Congress for permitting reform to advance renewable energy and transmission projects.

“I would say to people on the left who oppose permitting reform because they think it will lead to more unmitigated fossil-fuel-fired infrastructure, at this point it seems very clear from my vantage point that without permitting reform, what we are hindering is new zero-carbon energy sources,” he said.

My bold. What’s interesting about this is that if an Admin deems that it’s in the national interest, then it can override states. I wonder about Tribes. And according to this article, to environmentalists it’s more important to hold up fossil fuel projects than to increase “zero-carbon” energy. If the billions to build new transmission (from less politically powerful places to more politically powerful places) is coming from the taxpayer, would maintenance of those power lines also fall to the taxpayer? Lots of questions here, especially what regulations can do compared to Congress.

*******

Here’s the DOE press release:

DOE is also announcing up to $331 million through President Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to support a new transmission line from Idaho to Nevada that will be built with union labor—the latest investment from the $30 billion that the Administration is deploying from the President’s Investing in America agenda to strengthen electric grid infrastructure.

As the Federal government’s largest land manager, the Department of the Interior is working to review, approve and connect clean energy projects on hundreds of miles across the American West,” said U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland. “As we continue to surpass our clean energy goals, we are committed to working with our interagency partners to improve permitting efficiency for transmission projects, and ensuring that states, Tribes, local leaders and communities have a seat at the table as we consider proposals.”

The Biden-Harris Administration is tackling those challenges head-on, with today’s new CITAP Program and transmission investment announcement as the latest steps in broad efforts to take on climate change, lower energy costs, and strengthen energy security and grid reliability.

It sounds like maybe the energy costs will be lowered for, say the people in Nevada, but not so much, say Idaho. So Idaho gets the industrial infrastructure and the transmission lines, Nevada gets the energy.

My question is whether there might be a better way to build a clean energy future.. and whether the pros and cons of different alternatives (and costs and benefits) and- especially practicalities (availability of raw materials, supply chains, labor, maintenance) have ever been considered in a transparent way open to public review. Because I haven’t seen it and honestly it’s a bit hard to tell these policies from a solar and wind corporate taxpayer support program.

Anyway, the WaPo story here talks about Tribes and CBD wanting to halt construction on the Sun Zia line (mentioned above as an example of taking too long to permit):

The Tohono O’odham Nation has vowed to pursue all legal avenues for protecting land that it considers sacred. Tribal Chairman Verlon Jose said in a recent statement that he wants to hold the federal government accountable for violating historic preservation laws that are designed specifically to protect such lands.

He called it too important of an issue, saying: “The United States’ renewable energy policy that includes destroying sacred and undeveloped landscapes is fundamentally wrong and must stop.”

The Tohono O’odham — along with the San Carlos Apache Tribe, the Center for Biological Diversity and Archeology Southwest — sued in January, seeking a preliminary injunction to stop the clearing of roads and pads so more work could be done to identify culturally significant sites within a 50-mile (80.5-kilometer) stretch of the valley.

Attorneys for the plaintiffs have alleged in court documents and in arguments made during a March hearing that the federal government was stringing the tribes along, promising to meet requirements of the National Historic Preservation Act after already making a final decision on the route.

The motion filed Wednesday argues that the federal government has legal and distinct obligations under the National Historic Preservation Act and the National Environmental Policy Act and that the Bureau of Land Management’s interpretation of how its obligations apply to the SunZia project should be reviewed by the appeals court.

California-based developer Pattern Energy has argued that stopping work would be catastrophic, with any delay compromising the company’s ability to get electricity to customers as promised in 2026.